Return on investment by degree field: analysis shows clear winners and losers

Career earnings and wage growth are largely determined by the field students choose to study, government data shows.

An analysis of the data highlights which degrees boost earnings and which have the potential to burden students with debt.

As student loan debt continues to climb and tuition outpaces inflation, the value of a college degree is under sharper scrutiny.

A new Campus Reform analysis of undergraduate majors reveals that not all degrees offer equal financial returns, and some could potentially leave students with debt that far outweighs future earnings. By examining early and mid-career wages, wage growth, and graduate school dependence recorded in data from a 2025 report by the New York Federal Reserve, this review exposes which fields deliver strong return on investment (ROI) and which could saddle graduates with costly credentials and limited financial payoff.

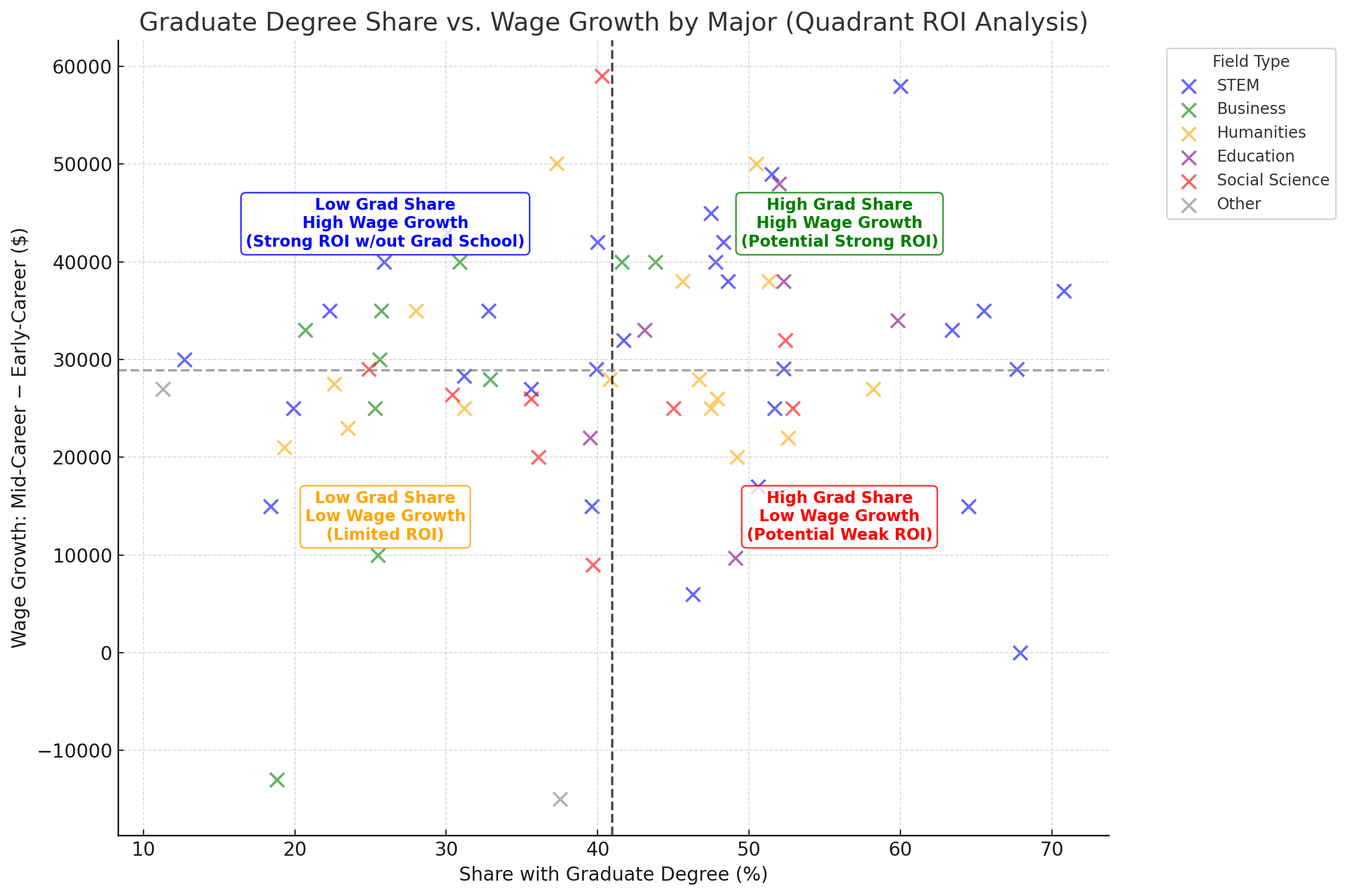

Graphs of the data illustrate the disparity between these educational paths and the wages they command. When plotted, wage growth and the share of graduate degrees place fields in one of four distinct quadrants showing the potential for a return on investment.

Created with ChatGPT

Created with ChatGPT

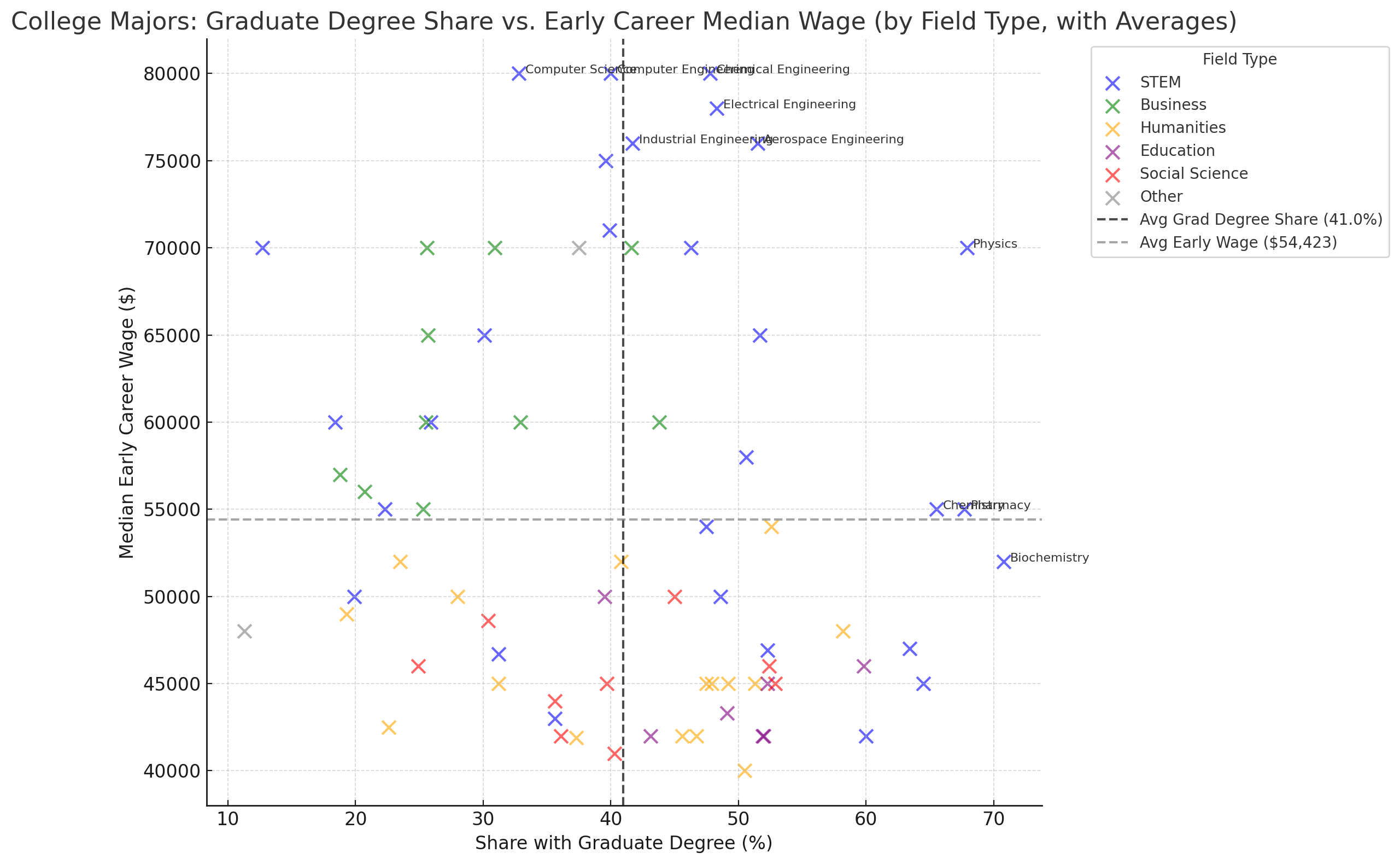

Looking at early- and mid-career wages reveals distinct outliers.

The graph below shows STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) disciplines dominate the highest range of early career median wages, although this landscape does begin to shift as careers progress.

Created with ChatGPT

Created with ChatGPT

While STEM populates the top of this graph, certain majors in that field also rank among the lowest.

STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math)

STEM fields may deliver the highest initial ROI, but not all majors are equal. Engineering disciplines dominate the top of the earnings spectrum, often exceeding six figures mid-career without requiring graduate degrees. By contrast, majors like biology and chemistry show more modest earnings and typically require further education to unlock competitive salaries. Math and physics also offer strong mid-career returns but often lean on graduate credentials to maximize income potential.

Most STEM majors fall in the “Low Grad Share / High Wage Growth” or “High Grad Share / High Wage Growth” quadrants, indicating strong ROI even without a graduate degree.

Examples such as computer engineering, electrical engineering, and aerospace engineering show mid-career wages exceeding $120,000 with early-career salaries above $75,000 and wage growth over $40,000.

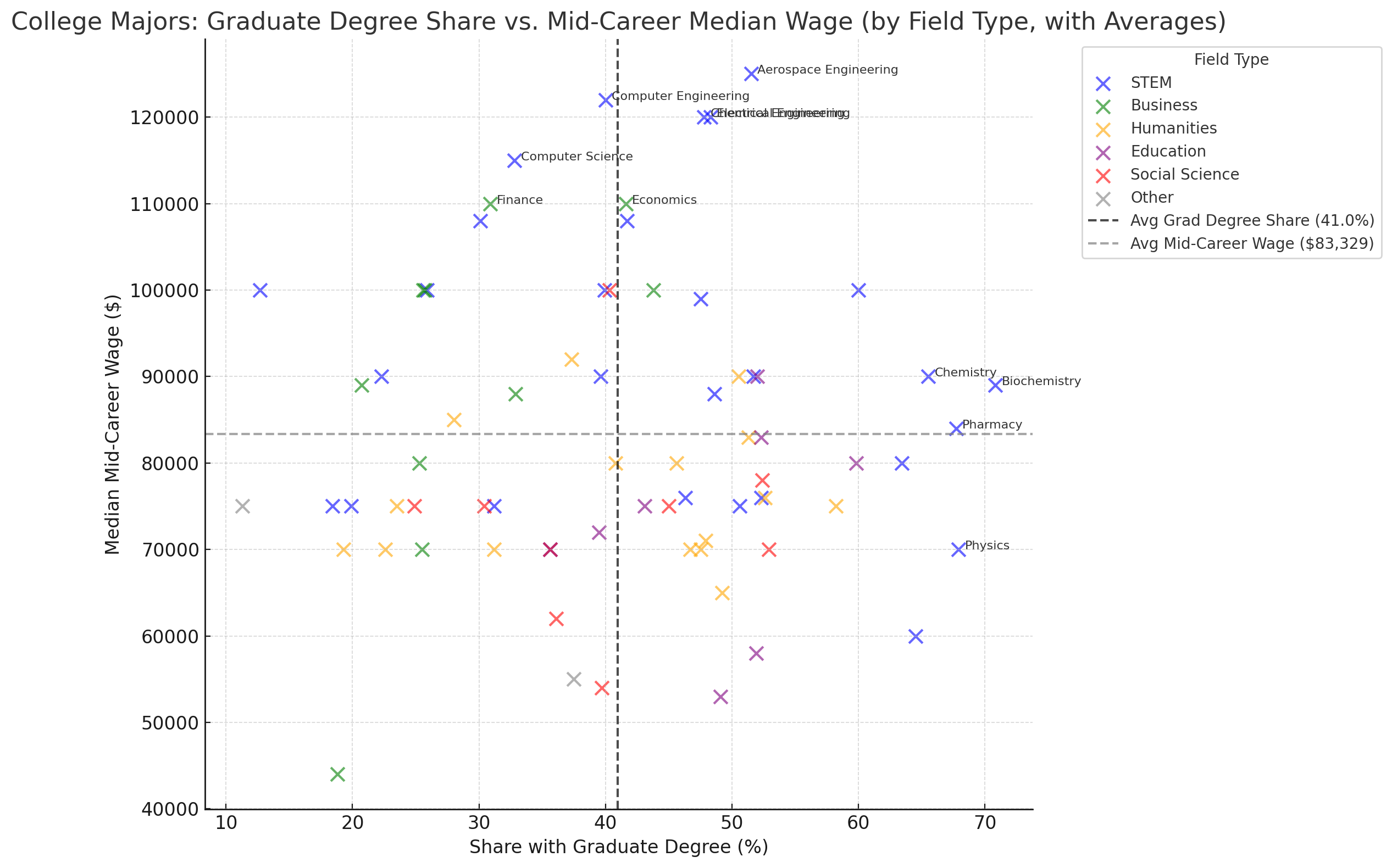

As seen in the graph below, other fields begin to catch up with STEM at the mid-career mark.

Created with ChatGPT

Created with ChatGPT

Business, with economics and finance at the head, is second to STEM disciplines. Other fields, including humanities and social science, begin to creep upwards at this point as well.

Business

Business majors consistently rank high in ROI, though the spread within the field is notable. Finance, accounting, and business economics provide robust wage growth and strong early-to-mid career salaries without the need for graduate school. In contrast, marketing and management offer respectable but lower pay trajectories, anchoring the field’s bottom range. These lower-tier business majors may cap out under $90,000 mid-career, despite similar tuition investments.

Data shows most business majors cluster in the upper-left quadrant, indicating efficient wage growth per degree cost.

Social Sciences

Social science majors show generally weak returns on investment compared to business and STEM fields. Degrees such as psychology, sociology, and political science tend to yield modest starting salaries and limited wage growth, with many graduates needing advanced degrees to approach median national earnings. Without graduate study, these majors often fall into the low-growth, low-wage category, highlighting the financial challenges within the field.

ROI is low, as many roles require graduate degrees but offer limited financial return. Early-career salaries are typically below $45,000, and mid-career wages rarely exceed $80,000.

[RELATED: DePaul hosts ‘anti-racism’ summer program for liberal arts freshmen]

Humanities

Humanities degrees present one of the widest internal ROI gaps—though all lean toward the low end. Philosophy and history tend to offer slightly higher mid-career salaries, especially for those who pursue law or graduate degrees. Meanwhile, majors like English, art history, and religious studies struggle to deliver wage growth, remaining concentrated in the lowest ROI quadrant. Even with further education, many humanities graduates remain below $100,000.

ROI remains weak, with graduate study rarely improving outcomes substantially. Early-career salaries are often in the low $40,000s, and mid-career pay seldom surpasses $80,000.

Education

Education is one of the most financially underperforming fields, largely due to the uniformity of its low ROI across subfields. Whether in elementary, early childhood, or special education, graduates start with modest salaries and experience limited wage growth over time. Most positions require advanced degrees or certifications, further eroding ROI. Few education majors exceed $70,000 mid-career, even with additional credentials, making it one of the least lucrative degree categories.

ROI is low, as many roles require graduate degrees but offer limited financial return. Early-career salaries are typically below $45,000, and mid-career wages rarely exceed $70,000.

Overall, the data show a sharp divide in the value of undergraduate degrees.

Fields such as STEM and business provide strong early- and mid-career salaries with robust growth and limited reliance on additional schooling.

By contrast, education, social sciences, and humanities carry a far weaker financial outlook. These majors often require advanced degrees just to reach median national earnings, but even with graduate study, wage growth remains limited. For many students, the added cost and debt of a master’s or doctorate erode the already modest return on investment.

The evidence suggests that pursuing a graduate degree only pays off in selective cases, such as in professional fields tied directly to higher wages or for licensing requirements. In most lower-return majors, graduate school represents more risk than reward, leaving many graduates with higher debt but little meaningful salary advantage.