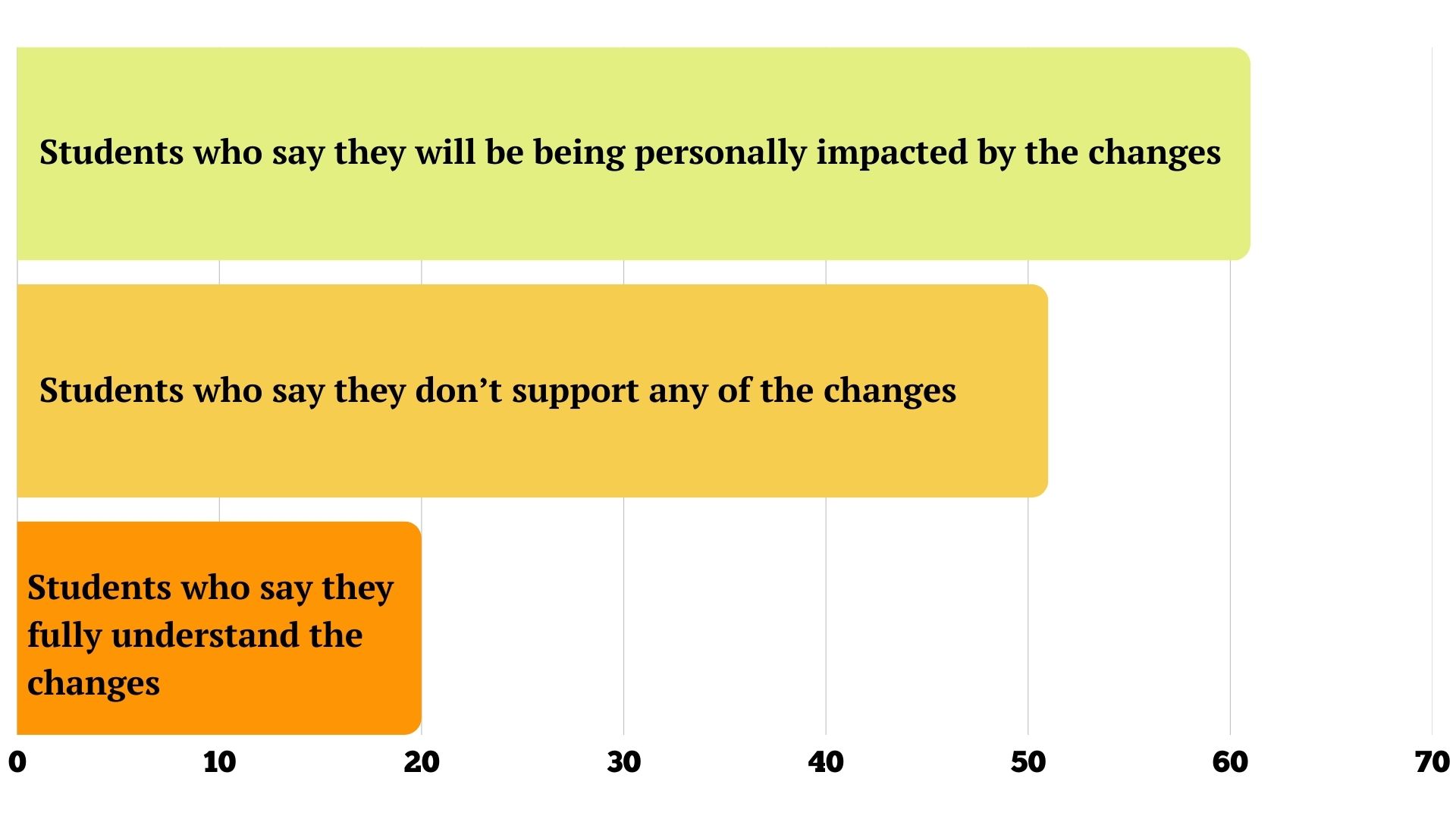

51% of students oppose new student loan laws, but only 20% say they 'fully understand' the rules: ANALYSIS

H.R. 1, or 'The Big Beautiful Bill,' eliminated the Biden-era SAVE Plan—an income-driven repayment option projected to cost taxpayers an estimated $475 billion over the next decade.

Easy access to cheap loans artificially inflated demand; limiting those loans should reduce demand and ideally lower costs, as basic supply-and-demand suggests.

When President Trump signed H.R. 1, colloquially known as the Big Beautiful Bill, on July 4, he eliminated the Biden-era SAVE Plan—an income-driven repayment option projected to cost taxpayers an estimated $475 billion over the next decade.

Now, at the start of a new school year, a contradictory trend has emerged among college students. A majority of college students, 51 percent, oppose all changes made to federal graduate loan lending, only a fifth feel they understand the new law.

Those numbers come from a U.S. News & World Report survey taken after H.R. 1 became law. While 61 percent of students anticipate being personally impacted by the law’s federal loan policy changes and 51 percent oppose all of them, only 20 percent said they “fully understand” what those changes entail.

[RELATED: Trump’s ‘Big Beautiful Bill’ overhauls student loans, introduces higher ed reforms]

Noah Jenkins, Chairman of the Tennessee College Republicans, told Campus Reform that most of the concern he’s experienced around H.R. 1 originates on social media and in the press due to the lack of nuance that coverage in many social media posts or news stories provide. Jenkins said the media doesn’t cover how “the changes HR 1 creates have the power to help lower higher education costs and our overreliance as a society on college.”

Titles from recent media coverage around H.R. 1 reflect the mainstream media’s wariness to get into the details on student loan policy: ”The Big Beautiful Bill is a Further Ugly Attack on Higher Education,” “Trump’s Big Bill Would Be More Regressive Than Any Major Law in Decades,” and “Sick Children Will Be Among the First Victims of Trump’s Bill.”

In addition to replacing SAVE with standard and “Repayment Assistance Plan” options, H.R. 1 also ends Grad PLUS loans and caps total borrowing at $100,000 for graduate degrees and $200,000 for professional degrees.

But those caps may prove healthy for a higher education system plagued by rising tuition rates and limited return on investment from degrees.

Jenkins expects more students to choose lower-cost programs that carry similar career value to elite ones, and more students who aren’t firmly committed to medicine, law, or similar fields will opt out.

“College often functions more as a credentialing requirement than as a pure educational pursuit,” Jenkins told Campus Reform. “Outside of some trades, a bachelor’s degree is usually the minimum for a stable and comfortable life.”

Easy access to cheap loans artificially inflated demand; limiting those loans should reduce demand and ideally lower costs, as basic supply-and-demand suggests.

”While students often describe H.R. 1 as unfair or unjust, I see those arguments as ways of justifying the more basic and practical fear about losing access to that credential,” he added.

But that fear has been stoked by colleges’ unhelpful reactions to H.R. 1’s passage.

36 percent of students said their college hasn’t been “transparent or helpful” regarding changes to the federal loan program. When asked whether the University of Michigan planned to adjust financial advising in response to the loan caps, Communications Manager Brian Taylor sent Campus Reform a link to the financial aid website. Here’s the website’s only mention of H.R. 1: “as information becomes available, the Office of Financial Aid will update this website.”

While universities generally do not provide direct guidance on private loans, they often point students to financial literacy programs. An upcoming fall 2025 program at Michigan titled “Enhancing Graduate Student Well-Being through financial education” says the presentation will be interactive, exploring what research has identified as a financial literacy gap among graduate students “particularly among underrepresented populations.”

Other sessions include “Leveraging Student Leadership to Create Inclusive Experiences for Diverse Communities in Higher Education” and “The Stigma of Mental Health and Illness in Academia.” There is no session dedicated to discussing H.R. 1.

“I’m so used to being in a community where everyone supports and encourages higher education,” said Alex Braun, officer-at-large of the College Democrats at Michigan. “So to see the opposite direction, to see a divestment in higher education from the federal government, is alarming and a little shocking.”

Braun is concerned that H.R. 1 will make it difficult for lower-income students to become doctors, especially amid what he believes to be a “doctor shortage” in the United States. His statement in The Michigan Daily links to an article about the physician shortage.

Residency slots, not loan limits, determine entry into medical practice. Medicare’s funding formulas—set using 1983 hospital cost reports and capped in 1997—distribute resources unevenly. New York receives nearly six times more funding per capita than Georgia while training only 3.5 times as many residents. Hospitals in New York average $139,000 per resident in Medicare support compared to $44,000 in Wyoming. This ineffective system, not federal loan caps, is the real barrier driving physician shortages.

Existing programs such as Public Service Loan Forgiveness and income-driven repayment spread costs across taxpayers, the vast majority of whom have not attended graduate school. Capping federal graduate loans does not bar lower-income students from medicine or law but shifts financing toward a mix of capped federal loans and private loans.

For a student with a credit score of 720+, a $100,000 Grad PLUS loan at 9.08 percent requires about $1,300 a month for ten years—$152,500 in payments. But because federal PLUS loans also charge an origination fee (about $4,200 upfront here), the true cost rises to roughly $157,000. By contrast, a private loan averaging 7.35 percent costs about $1,200 monthly, $141,500 overall—saving around $15,000, about 10 percent less than the federal option.

Federal loans remove risk-based pricing, so students with good credit often pay more than they would in the private market. Department of Education data show 10 percent of federal borrowers default within three years, and Pew Research estimates about 25 percent eventually default. Private loans, unlike federal ones, rarely include income-driven repayment, forgiveness, or long-term forbearance. This structure incentivizes borrowers to plan carefully, limit debt, and build credit early.

Campus Reform has reached out to Vanderbilt University and U.S. News. This article will be updated accordingly.